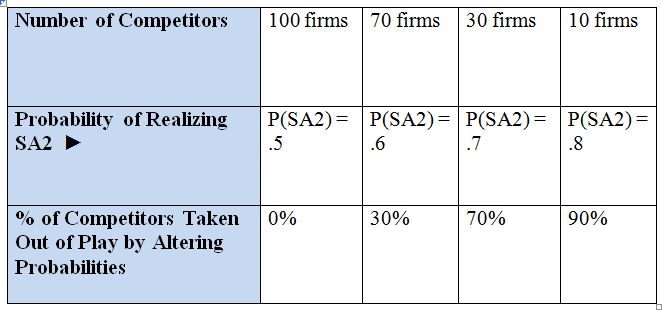

The chart above considers the effects of altering the probability of a firm’s realizing a projected state of affairs (SA2):

By altering firm’s probability of realizing SA2 from .5 to .6 – the number of competitors is reduced by 30 percent.

By altering firm’s probability of realizing SA2 from .5 to .7 – the number of competitors is reduced by 70 percent.

By altering firm’s probability of realizing SA2 from .5 to .8 – the number of competitors is reduced by 90 percent.

In other words, the competitive environment of the firm is literally altered by adjusting the probability that the firm will realize SA2. Adjusting the probability of the firm’s realizing SA2 not only increased the likelihood of the outcome the firm seeks, but also takes out of play 90 percent of the firm’s competitors.

Adjusting Probabilities

When any projected state of affairs has been realized, it has come into reality. It literally has been real-ized - 'made real'. States of affairs do not just pop into existence - they emerge from prior states of affairs logically and temporally ordered. States of affairs are dynamic configurations of elements and relations. The ordering necessary for realizing a projection must be such that the projection becomes increasingly probable as the transition unfolds. Interdependent states of affairs must be structured so that the occurrence of the earlier influences the occurrence of the later.

In our framework, following information-theoretic principles, we define causalities in this sense of probabilistically-related events; and we describe the interdependence of increasingly likely states of affairs as occurring by the use of patterns or structures. The probability of realizing a projected state of affairs is therefore affected by the nature of the configurations underway during the transition.

Different configurations of evolving states of affairs probabilistically relate to projections in differing degrees. Therefore, the probability of realizing any given projection is affected by the configurations of states of affairs the firm identifies and chooses to implement; and modifying or adjusting the elements and relations of those configurations literally changes the probabilities of the projection's occurrence.

In environments that are increasingly complex, elements and relations proliferate. In some cases, this imposes a cognitive burden on firms that jeopardizes their ability to effectively adjust probabilities. When this occurs, they can find themselves resorting to expediencies that make matters worse - for example, by too-readily following the herd movements of competitors. Our Pragmatica ontology enables firms to retain the cognitive poise needed to intelligently adjust probabilities notwithstanding the environment's often-disorienting pressures.